When I work with couples in distress, I often first need to put out some fires and get the couple out of crises before we can make any steps forward. If they are having sexual problems but have also built up so much resentment that they are fighting like cats and dogs, we can’t even begin to get to the sex stuff until we address the overall relational dynamic. I’ve written about this before in this article about why sex therapists must also be good couples therapists.

What I want to address in this piece are some of the mechanisms of how we can get a couple out of dire conflict and into a place where we can get some real work done. This requires achieving a safe space for both individuals, a sanctuary if you will. And it’s not small feat as we are in effect trying to transform a battlefield into a sanctuary. Wow, even writing that, it feels so daunting, like it would take something miraculous to pull off. But it doesn’t require miracles, but simply a process in which both partners are equally committed to putting aside attachments to who is right and wrong and putting in the necessary work to communicate more collaboratively.

There, that’s the magic word– collaboration. Which is so difficult for folks to pull off when they feel flooded and go into fight or flight response. Let’s talk more about collaboration and the fight of flight response when it comes to the way that couples communicate. I am indebted to the work of Dan Wile, and his writings on collaborative couples treatment for much of my thinking here.

Wile breaks down couples’ communication patterns into three main categories. The first two are highly toxic and unproductive and generally occur when one or both partners feel threatened and triggered. The first of these two is antagonistic communication. This means exactly what it sounds like. This is where individuals are harsh, critical, angry in tone, loud, and demeaning. It corresponds to the fight response of animals that feel threatened. Next is the withdrawal. This corresponds to the flight response. Examples include stating that nothing is wrong when it obviously is and then acting out in a passive-aggressive way, leaving the scene of the discussion, refusing to talk and shutting down. Stuff like that. Whereas antagonism is too aggressive, withdrawal is extremely avoidant.

It is often the case that antagonistic and withdrawal styles are found in the same relational dynamic. Antagonistic individuals may find themselves in partnership with withdrawing individuals, and their triggers fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. Classic push-pull dynamics that maybe some readers may have heard or read about. None of this stuff is productive, but I also want to make clear that it is not necessarily pathological or not normal. Indeed, we are wired to mobilize to fight or flee when we feel unsafe, so the issue here is not with our natural response to defend ourselves but rather with a more systemic issue of lack of (the subjective feeling of) safety within the relational framework. So what we must do is twofold: build more capacity to tolerate emotional triggers, and build more of an overall feeling of safety between the partners.

Let’s focus on the building of safety. We do this primarily through the third means of communication– confiding. Confiding communication requires the individual to stay present and discuss one’s feelings from a first-person point of view. It demands authenticity and the risk of exposing one’s vulnerabilities. Easier said than done when bullets are flying, right. Well, we want to start modeling this kind of behavior in the therapy room so that all partners can internalize the experience of hearing each other this way and then having more capacity to take these skills with them home. It takes time, it’s not going to happen overnight, but I want to start helping couples to have the lived experience of being able to communicate with each other on a different level, one that may initially only feel safer because it is being conducted in my consulting office.

Wile calls this “finding one’s voice” as opposed to the “losing one’s voice” that occurs when we are in fight/flight mode. So what may a confiding communication look like? Sometimes I may model it by speaking on behalf of one or both partners. So for example, for the withdrawing partner who has lost his/her voice and has become too triggered to be able to stay present in communication, I may say to the other person as if I was the partner, “I would like to tell how I feel but I am too afraid that you might get mad and reject me for it.” I would like both partners to hear what that sounds like; for the withdrawing partner to feel what it’s like to have voice given to one’s internal thoughts and for the antagonistic partner to perhaps hear these truths for the first time.

For the antagonistic partner, I might say, “I feel really hurt when you withdraw for me and I don’t know how to get my needs met without trying harder by showing you how mad and upset I am.” Something like that. Doesn’t have to be exact or perfect, just get the sense of it down. I may have both partners practicing in this way, finding ways of reclaiming their voice a little at a time by letting their partner peek into their authentic selves. And in this way we build safety because our minds seek congruence and when we have lived experiences, our minds form conclusions in order to explain these events. So when we take careful, measured risks of exposing our true selves in this kind of authentic way, and we are not hurt, and we are not rejected, but instead we see that the results are positive, we then start to transform our beliefs and conclude that we must be safe after all since our voice was heard and validated.

I’ll end here for now since I think I’ve made my basic point. There are three basic ways that couples communicate and the first two are tied into primordial animalistic responses to threat. By practicing the third type, confiding communication, we model a safe space in which we can work to mitigate and reverse the damage created by the first two ineffective modes of communicating.

Prevention: Is Sex Addiction Real?

Prevention: Is Sex Addiction Real? Romper: Emotional Infidelity

Romper: Emotional Infidelity Fatherly: BDSM More Common Than You Think

Fatherly: BDSM More Common Than You Think E! Online: Marrying a Murderer

E! Online: Marrying a Murderer Who Magazine: What is Bisexuality?

Who Magazine: What is Bisexuality? CNN: Why Men May Exaggerate Their Sex Numbers

CNN: Why Men May Exaggerate Their Sex Numbers Women’s Health: 10 Kinky Sex Ideas

Women’s Health: 10 Kinky Sex Ideas NY Post: How Tattoos Can Sabotage Your Love Life

NY Post: How Tattoos Can Sabotage Your Love Life Allure: 8 BDSM Sex Tips to Try If You’re a Total Beginner

Allure: 8 BDSM Sex Tips to Try If You’re a Total Beginner

Great article in Prevention Magazine about the sex addiction controversy. Check out what I had to say.

Great article in Prevention Magazine about the sex addiction controversy. Check out what I had to say.

Romper approached me again for another quote, this time about emotional infidelity.

Romper approached me again for another quote, this time about emotional infidelity.

Interesting piece in Fatherly about BDSM in which I was interviewed.

https://www.fatherly.com/love-money/bdsm-kinky-sex-not-uncommon/

Interesting piece in Fatherly about BDSM in which I was interviewed.

https://www.fatherly.com/love-money/bdsm-kinky-sex-not-uncommon/ E! News picked up my an interview I did with Vice a few years ago about hybristophilia, which is the attraction to criminals. Very interesting story.

E! News picked up my an interview I did with Vice a few years ago about hybristophilia, which is the attraction to criminals. Very interesting story.

Who is Australia's version of People Magazine. They wanted to know what bisexuality is and I provided some insight.

Who is Australia's version of People Magazine. They wanted to know what bisexuality is and I provided some insight.

Seems like something doesn't add up on sex surveys-- are men exaggerating their number of partners? Check out what I tell CNN.

Seems like something doesn't add up on sex surveys-- are men exaggerating their number of partners? Check out what I tell CNN.

Women's Health asked me for some kinky ideas to spice up one's sex life.

Women's Health asked me for some kinky ideas to spice up one's sex life.

I was interviewed by the NY Post about all the ways in which I've seen bad tattoos sabotage relationships.

I was interviewed by the NY Post about all the ways in which I've seen bad tattoos sabotage relationships.

Allure Magazine asked me about tips for BDSM beginners.

Allure Magazine asked me about tips for BDSM beginners.

I answer questions from Salon.com about the infamous porn site PornHub.

I answer questions from Salon.com about the infamous porn site PornHub.

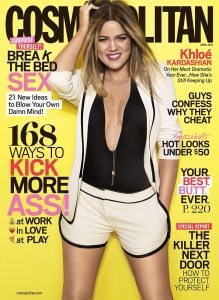

I tell Cosmo about the personality traits of monogamous individuals.

I tell Cosmo about the personality traits of monogamous individuals.

I explain to Refinery29 why it's so important to not fake orgasms in a relationship.

I explain to Refinery29 why it's so important to not fake orgasms in a relationship.

I am interviewed in this fairly nuanced piece on the pros and cons of porn.

I am interviewed in this fairly nuanced piece on the pros and cons of porn.

I am interviewed by Headspace, one of the best meditation and mindfulness apps available, on how to become more present.

https://www.headspace.com/blog/2017/05/26/enjoy-sex-more/

I am interviewed by Headspace, one of the best meditation and mindfulness apps available, on how to become more present.

https://www.headspace.com/blog/2017/05/26/enjoy-sex-more/ I am interviewed in this intriguing Business Insider article on how often happy couples have sex.

I am interviewed in this intriguing Business Insider article on how often happy couples have sex.

The Huffington Post in South Africa profiles my work around challenging sex addiction (including my red/yellow/green menu exercise) .

The Huffington Post in South Africa profiles my work around challenging sex addiction (including my red/yellow/green menu exercise) .

I go deep into the sex toy business with Vice.

I go deep into the sex toy business with Vice.

I give some insight into this interesting topic.

https://thetab.com/us/2017/03/22/happens-boyfriend-leaves-another-man-63306

I give some insight into this interesting topic.

https://thetab.com/us/2017/03/22/happens-boyfriend-leaves-another-man-63306 I am featured in this outstanding article in UK's Independent on women and virtual reality porn. I thought this was a fairly sharp and nuanced piece.

I am featured in this outstanding article in UK's Independent on women and virtual reality porn. I thought this was a fairly sharp and nuanced piece.

I give Redbook some pointers on having a 3some for the first time.

I give Redbook some pointers on having a 3some for the first time.

Playboy sent a journalist to watch Fifty Shades Darker, and then compared the movie with the results from my recent groundbreaking research on BDSM. Great article, enjoy!

Playboy sent a journalist to watch Fifty Shades Darker, and then compared the movie with the results from my recent groundbreaking research on BDSM. Great article, enjoy!

I am featured in this terrific New York Magazine article, discussing some of the finer points brought up in the earlier article in SELF magazine (see listing below).

I am featured in this terrific New York Magazine article, discussing some of the finer points brought up in the earlier article in SELF magazine (see listing below).

I am featured in this terrific article in SELF magazine on the nuances of the sex addiction debate.

I am featured in this terrific article in SELF magazine on the nuances of the sex addiction debate.

Complex asked me to weigh in on this provocative topic.

Complex asked me to weigh in on this provocative topic.

I weigh in in this great advice column in Thrillist by Elle Stanger.

I weigh in in this great advice column in Thrillist by Elle Stanger.

Great episode, check it out.

https://soundcloud.com/futureofsex/04-exploring-sexual-fluidity-bicuriousity-for-women-featuring-skirt-club-and-dr-michael-aaron

Great episode, check it out.

https://soundcloud.com/futureofsex/04-exploring-sexual-fluidity-bicuriousity-for-women-featuring-skirt-club-and-dr-michael-aaron I give couples advice on how to deal with differences in preferred sleeping arrangements.

I give couples advice on how to deal with differences in preferred sleeping arrangements.

Alternet does a great job of reviewing my book. Check out the link below.

Alternet does a great job of reviewing my book. Check out the link below.

In this episode, we talk about the societal myths of sexuality, including:

In this episode, we talk about the societal myths of sexuality, including:

I was asked to appear on Australian radio. It was a very fun segment, will post the link when I have it!

I was asked to appear on Australian radio. It was a very fun segment, will post the link when I have it! I appear on the Stereo-Typed podcast to discuss my new book, fantasies, and our shadow self. Click the audio player below and enjoy!

https://www.spreaker.com/user/crazyheart/stereo-typed-8-dancing-with-your-shadow

I appear on the Stereo-Typed podcast to discuss my new book, fantasies, and our shadow self. Click the audio player below and enjoy!

https://www.spreaker.com/user/crazyheart/stereo-typed-8-dancing-with-your-shadow I appear on the Boom Doctors Podcast to discuss my new book Modern Sexuality and my work as a sex therapist. Clink the link below to listen in.

http://theboomdoctors.com/2016/09/21/ep-132-michael-aaron-on-his-work-as-a-sex-therapist-his-new-book-modern-sexuality/

I appear on the Boom Doctors Podcast to discuss my new book Modern Sexuality and my work as a sex therapist. Clink the link below to listen in.

http://theboomdoctors.com/2016/09/21/ep-132-michael-aaron-on-his-work-as-a-sex-therapist-his-new-book-modern-sexuality/ I was asked by Nylon Magazine to weigh in on the subject of porn and what it means about the individual consumer. Pretty good non-pathologizing piece, check it out here:

I was asked by Nylon Magazine to weigh in on the subject of porn and what it means about the individual consumer. Pretty good non-pathologizing piece, check it out here:

I was interviewed by Vocativ about a new virtual reality series entitled "Virtual Sexology," designed to provide breathing and relaxation exercises in a virtual reality format to help individuals improve sexual functioning. Will something like this prove effective? The jury is out, but check out what I had to say...

I was interviewed by Vocativ about a new virtual reality series entitled "Virtual Sexology," designed to provide breathing and relaxation exercises in a virtual reality format to help individuals improve sexual functioning. Will something like this prove effective? The jury is out, but check out what I had to say...

I appeared on the nationally broadcasted Fusion Network Hotline show to discuss the GOP platform of porn as a "public health crisis." As part of the discussion I debate Dr. Neil Malamuth on porn and sexual violence. I thought this was a very thorough and productive half hour, which you can watch below:

I appeared on the nationally broadcasted Fusion Network Hotline show to discuss the GOP platform of porn as a "public health crisis." As part of the discussion I debate Dr. Neil Malamuth on porn and sexual violence. I thought this was a very thorough and productive half hour, which you can watch below:

In this Huffington Post article, I advise couples to use sex menus to spice things up. Check out all the details in the link below.

In this Huffington Post article, I advise couples to use sex menus to spice things up. Check out all the details in the link below.

I appeared on French national tv channel Canal + on the Emission Antoine tv show, discussing the psychology behind financial domination. I will post a video clip of the interview shortly.

I appeared on French national tv channel Canal + on the Emission Antoine tv show, discussing the psychology behind financial domination. I will post a video clip of the interview shortly. I was interviewed on Huffington Post's Love + Sex Podcast, which I'm told is the most downloaded sex and relationship podcast on iTunes. In this episode, I dispel the wild myths about "sex roulette" parties.

I was interviewed on Huffington Post's Love + Sex Podcast, which I'm told is the most downloaded sex and relationship podcast on iTunes. In this episode, I dispel the wild myths about "sex roulette" parties.

I was interviewed for an upcoming online sexuality discussion series, the Sexual Reawakening Summit. It features many top sex therapists from around the country and you can access it by using this link:

I was interviewed for an upcoming online sexuality discussion series, the Sexual Reawakening Summit. It features many top sex therapists from around the country and you can access it by using this link:  In the April edition of my Men's Fitness 'Sex Files' Q&A column, I answer questions about anal sex and porn. Hurry and pick up a copy before it's off the stands!

In the April edition of my Men's Fitness 'Sex Files' Q&A column, I answer questions about anal sex and porn. Hurry and pick up a copy before it's off the stands!

I was asked by Women's Health Magazine to provide some advise on how to incorporate some new positions to spice up one's sex life. With a bunch of pictures and diagrams, I'm sure you'll find something that will intrigue you.

I was asked by Women's Health Magazine to provide some advise on how to incorporate some new positions to spice up one's sex life. With a bunch of pictures and diagrams, I'm sure you'll find something that will intrigue you.

Looks like Yahoo News picked up the Reuters article on women's fears that their partners expect sexual perfectionism. Check it out.

Looks like Yahoo News picked up the Reuters article on women's fears that their partners expect sexual perfectionism. Check it out.

My latest interview with Reuters, this time about social pressure on women to be perfect sexually. "Our society is filled with sexual myths and misconceptions, mostly stemming from a combination of our culture's puritanical roots, as well as rampant consumerism, which feeds off individual insecurities to sell unnecessary products," Aaron said.

My latest interview with Reuters, this time about social pressure on women to be perfect sexually. "Our society is filled with sexual myths and misconceptions, mostly stemming from a combination of our culture's puritanical roots, as well as rampant consumerism, which feeds off individual insecurities to sell unnecessary products," Aaron said.

Head out to the newsstands and grab a copy of the Jan 2016 issue of Men's Fitness Magazine to see the premier of the new monthly "Sex Files" column in which I answer readers' sex questions. In this month's issue I answer a question in which a guy is looking to help his girlfriend enjoy more pleasure when she is having sex on top. Check out the screenshot below to see my response:

Head out to the newsstands and grab a copy of the Jan 2016 issue of Men's Fitness Magazine to see the premier of the new monthly "Sex Files" column in which I answer readers' sex questions. In this month's issue I answer a question in which a guy is looking to help his girlfriend enjoy more pleasure when she is having sex on top. Check out the screenshot below to see my response:

Love& is a new magazine about relationships and sex. They interviewed me about common things that women may want their guys to improve upon in the bedroom. One of the big ones is touch, as a lot of men are way too rough and don't know how to adjust their touch to what their partner wants. For more on this, and other pointers, check out the article itself below:

Love& is a new magazine about relationships and sex. They interviewed me about common things that women may want their guys to improve upon in the bedroom. One of the big ones is touch, as a lot of men are way too rough and don't know how to adjust their touch to what their partner wants. For more on this, and other pointers, check out the article itself below:

Market analysts predict that new virtual reality technology will revolutionize the way we experience media, and will specifically boost the porn industry to unprecedented levels. This detailed article covers a lot of ground, addressing both the technology, business and social ramifications of virtual reality porn. I was asked to give my take on the issue and somehow a 20 minute phone conversation was distilled to a brief paragraph at the end of the piece, but nonetheless, it is still a worthwhile read.

Market analysts predict that new virtual reality technology will revolutionize the way we experience media, and will specifically boost the porn industry to unprecedented levels. This detailed article covers a lot of ground, addressing both the technology, business and social ramifications of virtual reality porn. I was asked to give my take on the issue and somehow a 20 minute phone conversation was distilled to a brief paragraph at the end of the piece, but nonetheless, it is still a worthwhile read.

Does Bill Cosby have a fetish for unconscious women? Who knows? He's not a client and I've never met him, so I cannot say for sure, but this provocative piece in the NY Times tries to get to the bottom of his alleged bizarre behavior. The reporter did a great job dealing with some uncomfortable material, so be sure to click the link below to see what I had to say on this issue:

Does Bill Cosby have a fetish for unconscious women? Who knows? He's not a client and I've never met him, so I cannot say for sure, but this provocative piece in the NY Times tries to get to the bottom of his alleged bizarre behavior. The reporter did a great job dealing with some uncomfortable material, so be sure to click the link below to see what I had to say on this issue:

I was recently asked by a reporter from Men's Fitness magazine to discuss reasons why a heterosexual man might refrain from having sex with a willing woman. The questions were basically soft balls, seemingly aimed at a younger, more inexperienced, male audience, but hey, I managed to drop a few decent pointers, relating to finding out if the woman is in a relationship, and if so, what kind of relationship she is in before diving in. If you want to take a look and poke around more, you can go directly to the article below. You are going to have to click to page 3 to see my quotes, btw.

I was recently asked by a reporter from Men's Fitness magazine to discuss reasons why a heterosexual man might refrain from having sex with a willing woman. The questions were basically soft balls, seemingly aimed at a younger, more inexperienced, male audience, but hey, I managed to drop a few decent pointers, relating to finding out if the woman is in a relationship, and if so, what kind of relationship she is in before diving in. If you want to take a look and poke around more, you can go directly to the article below. You are going to have to click to page 3 to see my quotes, btw.

I was recently interviewed for a Men's Health article on sex toys designed for men. They wanted to know my take on these "robotic masturbators" (as they called them) and as always, I tried to take a fair and balanced view of things. I pointed out that they could be used as a way to get better acquainted with one's sexuality (as well as get some much needed relief), but an over-reliance on technology may also limit guys from developing the necessary skills that would help them form romantic relationships.

At any rate, hurry on over to the article here--

I was recently interviewed for a Men's Health article on sex toys designed for men. They wanted to know my take on these "robotic masturbators" (as they called them) and as always, I tried to take a fair and balanced view of things. I pointed out that they could be used as a way to get better acquainted with one's sexuality (as well as get some much needed relief), but an over-reliance on technology may also limit guys from developing the necessary skills that would help them form romantic relationships.

At any rate, hurry on over to the article here--  Go check out a great, and I mean GREAT, absolutely fascinating article in the May issue of Upscale Magazine, entitled "Secret Lovers," in which I am interviewed regarding the hush hush world of the swinger subculture. The writer does a really good job of trying to understand the psychology of folks who practice consensual non-monogamy and I think the piece is very even-handed, with some practical tips for couples who are curious about dipping their toes in the lifestyle. I'll leave you with a quote from one of the swingers profiled in the piece, which I think gives a good feel for the tone and depth of the article-- "I love to see her with two guys and two girls at once. I enjoy submissive women, and there is no sexier submission than to watch my wife please me by pleasing others." If that sounds interesting, then I suggest you head out and grab a copy. It's well worth the read.

Go check out a great, and I mean GREAT, absolutely fascinating article in the May issue of Upscale Magazine, entitled "Secret Lovers," in which I am interviewed regarding the hush hush world of the swinger subculture. The writer does a really good job of trying to understand the psychology of folks who practice consensual non-monogamy and I think the piece is very even-handed, with some practical tips for couples who are curious about dipping their toes in the lifestyle. I'll leave you with a quote from one of the swingers profiled in the piece, which I think gives a good feel for the tone and depth of the article-- "I love to see her with two guys and two girls at once. I enjoy submissive women, and there is no sexier submission than to watch my wife please me by pleasing others." If that sounds interesting, then I suggest you head out and grab a copy. It's well worth the read. I am featured in the Sex Q&A section of Cosmo's April 2014 issue, in which I get asked about BJs, Plan B, sex in hot tubs, and all kinds of other tittilating reader questions. They did a good job of adding all kinds of humor, including a silly picture of tea bags-- need I say more? It's a can't- miss hoot. Go and check it out at news stands now!

I am featured in the Sex Q&A section of Cosmo's April 2014 issue, in which I get asked about BJs, Plan B, sex in hot tubs, and all kinds of other tittilating reader questions. They did a good job of adding all kinds of humor, including a silly picture of tea bags-- need I say more? It's a can't- miss hoot. Go and check it out at news stands now! I just recently did an interview for a cool podcast called

I just recently did an interview for a cool podcast called